Adams County and the Great Depression Milk Strike

Farmers in 1933 Stopped the Flow of Products to Market; Shut Down Creameries.

By Harry Davis

Some of us remember the Milk Strike of 1967 sponsored by the National Farm Organization (NFO), but the 1967 strike was a walk in the park compared to the strike that those 1967 farmer’s fathers experienced in 1933. That strike was born out of the desperation of the Great Depression, but for Adams County, it was a lesson on how working together builds community.

Bad Times Building

By the beginning of the year 1933, and the start of the Franklin D. Roosevelt presidency, the Wisconsin dairy farmer had already been whiplashed for over a decade by steadily falling product prices, rising costs of production, threats of mortgage foreclosures, bank failures and impatience with waiting for a promised New Deal from the government.

Still, Adams County dairy farmers and Wisconsin farmers generally were more restrained than farmers elsewhere. There had already been farm product strikes in New York, Iowa, Illinois and Indiana before there was any action in Wisconsin.

Wisconsin first became involved in the farm protest when Dunn County’s Arnold Gilberts of the Wisconsin Farm Holiday Association addressed some 5,000 farmers at a rally in Marshfield on September 2, 1932. Gilberts was quoted as saying at the rally, “We’ll solve our problems with bayonets, and I don’t mean maybe.”[1]

The Wisconsin Farm Holiday Association claimed a large membership of 130,000 out of a total of 180,000 Wisconsin farms. Another group, the Wisconsin Co-operative Milk Pool, led by Walter M. Singler of Shiocton, had many fewer members (6,700) than the Farm Holiday organization, but was a more radical group. Both organizations were active in Adams County in 1933.

First Strike

The first milk strike of 1933 occurred in February. It was called by Singler’s Milk Pool. Singler, hoping to affect prices by simply withholding product, announced that the farm price for milk would be $1.40 per hundred starting the morning of February 15th. All farmers were supposed to hold their milk for that price, but many did not and the Milk Pool moved towards more direct action.[2]

The first milk strike of 1933 occurred in February. It was called by Singler’s Milk Pool. Singler, hoping to affect prices by simply withholding product, announced that the farm price for milk would be $1.40 per hundred starting the morning of February 15th. All farmers were supposed to hold their milk for that price, but many did not and the Milk Pool moved towards more direct action.[2]

Milk began being dumped along highways, roads were barricaded, milk trucks were stopped and turned back by armed men, and small cheese and butter factories were closed down in the Fox Valley. Adams County farmers were undoubtedly involved in some of the action taking place at that time of year but their actions were either unknown or willfully ignored by the local paper.

The first mention of the Milk Strike in the Friendship Reporter came as an appeal in late March to stop striking. The paper quoted Thomas O’Connor of Clintonville, president of the Pure Milk Products Cooperative (membership 3,200) saying, “Farmers of Wisconsin and elsewhere should not strike before giving newly elected national and state leaders ample opportunity to adjust farm conditions.”[3] He went on to suggest that farmers themselves would suffer the most saying, “In the recent milk strike many farmers joined, not because they wanted to, but because they feared bodily violence and destruction of property if they refused to join.”[4]

If at First You Don’t Succeed

Whether the farmers joined the strike out of fear or out of dedication, the strike was having an effect on politics if not on prices. Wisconsin Governor Schmedman rushed to Washington to meet with President Roosevelt and Agriculture Secretary Wallace, and then back to Chicago to attend an interstate governor’s conference on the farm strike issue.[5]

While the governor was meeting in Chicago, the Milk Pool was meeting in Appleton planning a strike to begin May 10.[6]

Also at the same time, Adams County farmers and other home owners were meeting in the courthouse to hear a talk by Wisconsin Farmers Holiday Association President, Arnold Gilberts. Gilberts told the large group assembled about the work that the Holiday Association had already accomplished and told of legislation that organized agriculture was demanding of the new federal government. He made it clear, according to the paper, that farmers would not accept substitute legislation written by people who knew nothing or cared nothing about the farmers needs.[7] Gilbert then asked attendees to write their representatives urging them to support the Frazier Bill that would provide relief from mortgage foreclosures.[8]

The Milk Pool was serious about the May Milk Strike even if the Holiday Association was not. This time The Friendship Reporter did report Adams County involvement. The paper announced that a series of meetings were to take place the week preceding the start of the May strike the governor was trying to avert. Milk Pool Treasurer, H.F. Dries was scheduled to speak Monday, May 8 in the Quincy Town Hall, Tuesday May 9 at the Arkdale Town Hall and Wednesday, May 10 in the Dell Prairie school house. Milo Singler was to speak Monday, May 8 at the Monroe Center Town Hall, Tuesday, May 9 at the Easton Town Hall and Wednesday, May 10 at Tabbert’s Hall in Brooks.[9]

To the Barricades! Or Not.

The May Milk Strike hit with a vengeance, but not in Adams County because Adams County was not included in the state wide strike zone. Either the Milk Pool meetings held in Adams County did not convince farmers to strike, or it was decided that striking other areas was a better tactic. John Tuttle, the Friendship Creamery owner told the paper that he had not closed operations and that only two of his 200 patrons were holding cream because of the strike.[10]

The May Milk Strike hit with a vengeance, but not in Adams County because Adams County was not included in the state wide strike zone. Either the Milk Pool meetings held in Adams County did not convince farmers to strike, or it was decided that striking other areas was a better tactic. John Tuttle, the Friendship Creamery owner told the paper that he had not closed operations and that only two of his 200 patrons were holding cream because of the strike.[10]

Elsewhere, violence broke out. National Guardsmen with machine guns and bayonets, and sheriffs and deputies clashed with farmers in Shawano County where 68 farmer picketers were captured. At Durham Hill in Waukesha County, guardsmen with bayonets dispersed a large crowd after deputies failed to do so using gas bombs.[11]

After the May 1933 strike milk prices rose slightly for two months, and then fell again in August unleashing another strike threat. During the period the price of butter rose to 26¢ a pound then fell back to 19¢ a pound.[12] Discussions, accusations, and promises continued into the fall, but nothing brought a resolution to the dairy crisis.

Adams County farmers’ patience finally ran out in late October. Adams County Farm Holiday Association President Bert Olsen ordered all members to withhold their milk the week of October 22-28. Olsen then conferred with the owners of the Arkdale and Friendship creameries and persuaded them to close their businesses on Saturday night October 28.[13]

Adams County farmers’ patience finally ran out in late October. Adams County Farm Holiday Association President Bert Olsen ordered all members to withhold their milk the week of October 22-28. Olsen then conferred with the owners of the Arkdale and Friendship creameries and persuaded them to close their businesses on Saturday night October 28.[13]

Friendship Creamery owner John Tuttle shut down his operations that Saturday saying that he figured it was a wise move to stop operations and abide by the Holiday’s ruling until his supply on hand was moved. He also complied with the Holiday Association’s demand that the price of butter be raised to 39¢ a pound. Tuttle dutifully included the additional amount in the farmers’ cream checks even though he was not associated with any association or union whether involved with the strike or not.[14]

The creameries were not closed for long. Local Holiday president Bert Olsen received a telegram from Wisconsin Association President Arnold Gilberts instructing him to discontinue the strike as of Wednesday morning, November 1st. Gilberts sent the telegram from Des Moines, Iowa where he was attending a governor’s conference that seemed to hold the promise of favorable crisis resolution for the farmer. The Adams County and other creameries reopened on November 1st. The price of a pound of butter immediately dropped to 27¢[15] setting the stage for what happened next.

Violence Comes to Adams County

Although strike leaders had proclaimed that violence would end and farmers would merely withhold their products from the market, mischief continued; even in Adams County. Because law enforcement officers were breaking up highway blockades and bringing out the National Guard in anticipation of announced actions, picketers adopted a hit-and-run style of attack. They would surprise and commandeer unprotected milk trucks, dump the products and quickly disappear.

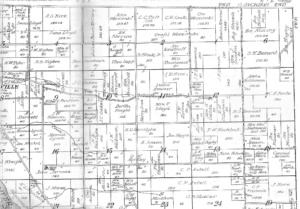

Such an attack took place in Dell Prairie on Monday, November 6, 1933. Robert Murray, a route driver for the Kilbourn Co-operative Creamery of Wisconsin Dells came upon a large group of hit-and-run picketers as he approached the Bement farm on County Road “B” at Davis Corners. As he was driving on to the farm property, the picketers climbed on the truck, smashed windows and threw products off the back. Murray drove around the house and back toward the main road without stopping, but the truck went into the ditch beside the road. Murray finally got the truck back on to the road and went straight back to Wisconsin Dells. The 17 men involved in the attack were not identified.[16]

Lawyers for Kilbourn Co-op and Robert Murray filed claims for damages with the Adams County Board of Supervisors the following week. The Co-op asked for $350 alleging that 900 pounds of cream and other products were destroyed and glass was broken on the windshield, rear window and right door of the truck. Murray asked for $4,000, claiming a brain concussion and other personal injuries. The County Board disallowed both claims stating that the county was not responsible for the damages.[17]

Strikes End with Concern for Farm Families

The Wisconsin milk strikes of 1933 ended on Saturday, November 18, 1933 with a joint declaration by the Wisconsin Farmer’s Holiday Association and the Wisconsin Co-operative Milk Pool. Following the announcement ending the strikes, the declaration went on saying, “We reaffirm our previous stand and maintain our demands for economic justice. We particularly urge our membership not to increase their misery by contracting further debt in any form by mortgaging or assigning what little property they have left and to care first of all for their families and cooperate with each other in maintaining possession of their homes.”[18]

After Thought

The frustration and desperation that led farmers to strike in 1933 is understandable. From our current vantage point, knowing what those people could not know; that is, what the future would bring, the futility of the violence that accompanied the strike for what little was gained seems hard to justify. If we could stand in our grandparents’ shoes however, and face the inability to feed, shelter and support our family, not knowing what the future would bring, we would likely feel and act as they did.

We of Adams County can point with some pride to the cooperation between the Adams County farmers and the Adams County creameries that prevented more violence from occurring here. A lesson, perhaps, for all times.

____________

This article previously appeared in the Adams County Historical Society’s

[1] Jacobs, Herbert Austin, “The Wisconsin Milk Strike” Wisconsin Magazine of History, Volume 35/Issue 1 (1951-1952) pp. 30-31

[2] Ibid, page 32.

[3] “O’Connor says to Halt Milk Strike”, The Friendship Reporter, Thursday, March 30, 1933.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Schmedeman Maps Plan to End Milk War”, Friendship Reporter, Thursday, April 13, 1933.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Farmers Meet Well Attended”, Friendship Reporter, Thursday, April 13, 1933.

[8] Ibid. The “Frazier Bill” led to the Frazier-Lemke Farm Bankruptcy Act and other laws aimed at forestalling mortgage foreclosures. These legislations eventually led to the formation of the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) in 1938 to assure a consistent supply of mortgage funds.

[9] “Milk Pool Will Hold Meetings”, The Friendship Reporter, Thursday, May 4, 1933.

[10] “Open Warfare in Milk Strike”, The Friendship Reporter, Thursday, May 18, 1933.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “State Farm Board reports on findings”, The Friendship Reporter, Thursday, August 31, 1933.

[13] “Strike Now Hits Adams County”, The Friendship Reporter, Thursday, November 2, 1933

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “First act of Violence Appears in County at Davis Corners”, The Friendship Reporter, Thursday, November 9, 1933.

[17] “Two Claims Totaling $4,350.00 Faces County As Result of Strike Violence”, The Friendship Reporter, Thursday, November 16, 1933.

[18] “Strike Called Off Saturday”, The Friendship Reporter, Thursday, November 23, 1933.