Railroads in Adams County

On The “Air Line”

“Nothing is more conspicuous in the development of a country than the building of railroads…nothing in the way of products or resources begins to count until the railroads come along…. then new towns spring up almost in a night, rich farms are developed, factories are put in operation and the wilderness becomes a garden of wealth.”

J.E. Jones, Kilbourn Events, 1910.

J.E. Jones, Kilbourn Events, 1910.

Adams was the last county in Wisconsin to have a railroad within its borders, but the history of railroading here is almost as old as the history of railroading in the entire state. It begins in 1856, with settlement underway in Adams County, and one of Wisconsin’s first railroads, the La Crosse and Milwaukee, laying track across the state.

After reaching Portage, work on the “La Crosse Road” halted while engineers looked for an opportune place to cross the Wisconsin River and management searched for a way the nearly broke railroad could finance it. The President of the La Crosse and Milwaukee was Byron Kilbourn, one of the founders of Milwaukee and a genuine American “robber baron.” He was an avid perpetrator of the farm mortgage scheme, whereby farmers in the area where a railroad was proposed would finance construction by buying railroad stock. Since cash money was in short supply on the frontier, the farmers had to mortgage their land to buy stock. Acting as broker, the railroad would then sell the mortgage notes to eastern financiers and use the cash to acquire right-of-way, lay track, purchase equipment and pay a good salary to executives like Byron Kilbourn. Interest on the mortgages, plus earnings for the farmers, would be paid by dividends from the railroad when it started operating. If and when the railroad earned a profit, as it would no doubt, so would the farmers–at least according to the sales pitch.

Stock salesmen fanned out from Portage into Sauk, Columbia, Juneau and Adams counties, where the settlers would have agreed with J.E. Jones had they heard him say that, “Nothing is more conspicuous in the development of a country than the building of railroads…”

In Sauk County, the stock salesmen told farmers that the railroad would run from Portage to Baraboo, Reedsburg and beyond. In Columbia and Juneau counties they told farmers the railroad would run up the Wisconsin to the village of Newport, where Lake Delton is now located, then cross the river and turn north. This promise led to intense speculation in Newport where the value of a city lot rose from $85 to $1,000.

In Adams County the salesmen told farmers that the railroad would run up the Wisconsin to Point Bluff, where it would cross the river and head west along the Lemonweir River. Railroad dreams led the Methodists to build their school at Point Bluff, which they believed would be the site of a bustling city thanks to the railroad. Sophronia Temple, who farmed near Plainville with her husband Timothy, wrote to family in Massassachusetts in 1856 that the railroad would run “acrost my farm”…when it is done we shall be in town, I shall be only three days from Boston. I should like to have you all come and see me at the grand opening.”

Expectations such as these were good for stock sales throughout central Wisconsin. The La Crosse and Milwaukee acquired about $1.1 million in farm mortgages, including a few thousand from Adams County. There was a hitch, of course. Despite the promises of the stock salesmen, the railroad could cross the Wisconsin in only one place and that one place turned out to be the new village owned by and named after Byron Kilbourn. In 1857, the railroad crossed the river at Kilbourn–now Wisconsin Dells–and then pushed on to Lyndon, Mauston, Tomah and La Crosse. Promises made to farmers in other places were not kept, which would not have been a disaster had the La Crosse and Milwaukee turned a profit and paid a return on its stock. Instead, the La Crosse and Milwaukee, along with every other railroad in the state, went bankrupt in the depression of 1857, defaulted on its bonds and left the farmers liable for their mortgages. “In the history of the financial speculations of this country so bold, open, unblushing frauds, taking in a large body of men, were never perpetrated,” said Governor Alexander Randall, of the farm mortgage scheme.

Adams County farmers suffered no more from the “unblushing frauds” than others in central Wisconsin, although the experience kept them leery of promises made by railroaders for decades. The serious loss to Adams occurred when the railroad bypassed the county. It meant, for example, that farmers in the southern part of the county would trade in Kilbourn/Wisconsin Dells instead of at a market town inside the county. It was the first instance in which Adams County trade would be used, as Friendship newsman Harry Pierce said, to “help build up outside towns.”

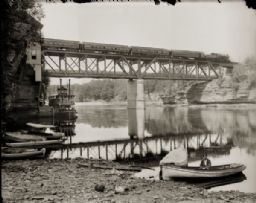

It was not the last. The La Crosse & Milwaukee, reorganized and nicknamed the “Milwaukee Road,” came back from bankruptcy and, in 1873, reached Necedah on its way to Nekoosa. Ten years later Necedah got another railroad when the Chicago and North Western line was extended east from Wyeville. In short time, farmers and merchants on both sides of the Wisconsin River wanted a bridge at Petenwell Rock. It was built in 1882 and farmers from Strongs Prairie and Monroe loaded their wagons and headed west to trade in Necedah, which became another out-of-county market town for Adams County people.

The Civil War delayed railroad expansion, but work resumed when peace returned. In central Wisconsin, railroad builders were encouraged by a federal land grant that promised to award one square mile of public land for every mile of track laid from either Neenah/Menasha or Portage to the shore of Lake Superior. Adams County joined in lobbying for the grant and sent Thomas Marsden of Friendship to the legislature in 1865 in hopes that he could route the railroad to his home town.

After a few years of politicking, scheming and other form of chicanery common in the annals of pioneer railroading, the legislature awarded the land grant to the original Wisconsin Central Railroad, which laid track from Neenah to Stevens Point and Marshfield in 1871 before turning north to Ashland. In Stevens Point, the Wisconsin Central illustrated the power of a railroad to make a city and why Adams boosters wanted tracks inside county lines. Prior to the Central’s arrival, Stevens Point had about 1,000 people and a few sawmills. Five years later, nearly twenty mills were at work and the population had grown to 4,551.

While still on the way to Ashland and in order to claim as much of the land grant as possible, the Wisconsin Central also built a branch line from Stevens Point to Portage. Although Adams County leaders reminded the Central that it would earn more granted land by diverting the line to Friendship, the railroad refused. The best it would do was build a depot at Liberty Bluff, sixteen miles due east of Friendship and about five miles into Marquette County. All Adams County had to do was improve the wagon road from Pilot Knob to Friendship, which the county supervisors agreed to do in 1876. This road later evolved into a state highway and then became County Highway J. The completion of the Stevens Point-Portage line now meant farmers in eastern Adams County could trade in Plainfield, Hancock, Coloma, Liberty Bluff or Westfield, all served by the Wisconsin Central and all out of the county.

Thirty years after it was organized, Adams County was surrounded by railroads, but a railroad had yet to enter the county. As a result, growth and development all but halted. The sheer difficulty and snail’s pace of transporting goods by horse and wagon made every item produced in Adams County harder to market and every item sold here more expensive. In 1860, the population of the county hit 6,492. In 1890, it was 6,889, revealing the slowest growth of any county in the state. Friendship, still unincorporated and with fewer than 300 people, was the smallest county seat in Wisconsin and the only one not to have a railroad.

County people attempted to improve the situation. Between 1870 and 1900, the air was hot with railroad talk, but cold on railroad action. In 1871, the Madison and Portage Railroad pledged to lay track from Portage to Friendship–with help from $45,000 in new bonds issued by the county. But one year later, after seeing no work on the line, the county board recalled its bonds.

In 1874, someone laid a ruler on the map and saw that Friendship was on the “air line” from the Chicago and North Western railhead at Princeton in Green Lake County to St. Paul, Minnesota and local people hoped that track would be laid–to no purpose. In the 1880s, over 2,000 miles of rails were spiked down in Wisconsin–none in Adams County. As the 1890s dawned, the county board issued a blanket invitation and a promise of public aid to “any railroad” to build in the county. None accepted the offer, but neither hope nor speculation diminished in Adams County.

In November 1892, the Adams County Press published a notice of “railroad rumblings” that inspired a decade of speculation related to the “Princeton line.” The paper reported that “one of the chief engineers of the Chicago and North Western Railroad” was supervising a crew “to drive the stakes” for a “permanent line” from the North Western’s terminus in Princeton to Necedah by way of Friendship. The line was surveyed to approach Friendship from the southeast either along or just south of what later became Airport Drive and continue northwest through the village and beyond. It would cross the Wisconsin just south of the mouth of the Big Roche-A-Cri in Strong’s Prairie at “Carmon’s Rock”

“This looks as if the C & NW people mean business for sure this time,” said the Adams County Press, and other newspapers agreed. The La Crosse Tribune opined that the North Western needed a new through line across the state so it could ship coal from Sheboygan to the Mississippi River. The Fond du Lac Reporter said that the North Western had to build a new line soon since all its present trackage was overburdened with traffic headed for the Chicago World’s Fair. The definitive word came from the Milwaukee Sentinel which stated, “There is no question that the road will be built this coming season…”

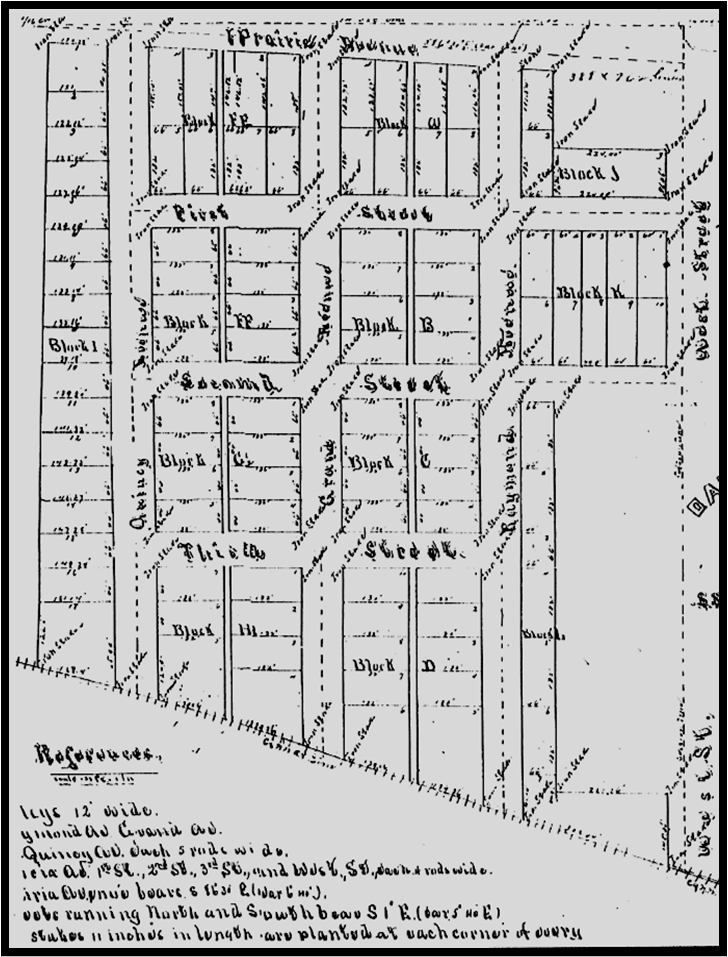

Friendship’s chances looked so good–at least in the newspapers–that County Treasurer Sophronius Landt, hotel keeper William Knight and newspaper editor Solon Pierce platted the Oak Lawn subdivison on the west side of the village. It was bounded on the north by “Prairie Street,” (now County J) and on the south by the railroad right-of-way which ran roughly from the present corner of Fifth and West Street to Fourth and Quincy. Appropriately, one of Oak Lawn’s north-south streets was named “Raymond” in honor of the railroad engineer who supervised the survey that prompted the excitement.

Railroad fever was contagious. In the spring of 1893, so many new homes were going up in Oak Lawn the Press reported that two blocks “look like a lumberyard.” The editor of the Westfield Central Union newspaper reported that, “Our neighbors up at Friendship are as much elated over their prospect of a Railroad as though it were a reality…plating additions, tearing down Chimney Rock…” This last was a reference to Peter Sorenson’s unsuccessful attempts to quarry stone out of Friendship Mound by means of blasting powder.

“They have a pleasant little burg and a select class of people,” continued the Westfield editor, “whose average moral quality will not be improved by the influx that will come with the railroad.” He needed have worried. By the end of the summer of 1893, the latest outbreak of railroad fever was on ice. The North Western did not carry it plans beyond the survey stage in Adams County and instead ran a new line from Princeton to Wautoma and Wisconsin Rapids. In Adams County, the North Western’s “Princeton” line became another entry in the long list of phantom railroads unbuilt.

By the turn of the century, the railroad situation had not changed, but other conditions in the county had. With the best farmland in the state already settled, landlookers who once bypassed the dry sands and wet peats of Adams County gave them another look. Settlers born in the United States and immigrants from Bohemia, Germany, Poland and other parts of Europe took up farms in Adams County. Towns that saw the greatest increases were Rome, Leola, Richfield, Preston and Big Flats. So many new settlers had moved to Leola and Richfield that a new town, Colburn, had to be created in 1891. Rome, which had no more than 232 people in 1890, grew to 654 in 1900. The population of the entire county grew to 9,141 in 1900, an increase of nearly one-third since 1890.

Farming, the occupation practiced by an overwhelming majority of the county’s people, had also developed. The county had 1,393 farms in 1895. Dairying was developing, along with cash-cropping of potatoes and rye. At the state fair in 1901, Adams County produce was described as “unsurpassed by any other county.”

With a growing population and farming developing, the county was ripe for a new wave of railroad speculation. In 1900, a company headed by R. A. Crandall and W. S. Syrett revived the old Princeton “air-line” concept, looked up the survey completed by the North Western in 1893 and organized the Princeton and Wisconsin River Railroad. Taking up the county’s decade-old offer to provide aid, they submitted a petition bearing 1182 names calling for the county to issue bonds to buy $100,000 of stock in the new railroad and presented it to county clerk R. S. Harrison. He dutifully filed it in his office in the stone building on the courthouse lawn, while railroad boosters set out to persuade the county board to accept and act on it.

Instead of fever for a railroad, this version of the “Princeton Line” encountered opposition hot enough to inspire criminal behavior. On the night of December 12-13, 1900, a burglar broke into the office of the county clerk, ransacked the files and made off with the railroad petition. Suspecting that the burglary was a deliberate attempt by its opponents on the county board to kill the railroad and that it could prove a criminal conspiracy to do so, the Princeton and Wisconsin River filed suit. In June 1901, the circuit court sitting in Wautoma, heard the case of what one editor called “the Adams County Railroad Rumble.”

The railroad was represented by lawyers from a Milwaukee firm. The anti-railroad majority of thirteen county board supervisors sent district attorney John Purves to represent its interests, while the pro-railroad minority of four sent the now venerable Solon Pierce. After examining information obtained from a copy of the stolen petition, the judge determined that at least half the names on the petition were either men ineligible to vote, women who had no voting rights or people of no gender since they were dead at the time they supposedly signed their names. Therefore, despite the dubious circumstances of the burglary of the county clerk’s office, the petition was invalid and Adams County was not obliged to aid the Princeton and Wisconsin River Railroad.

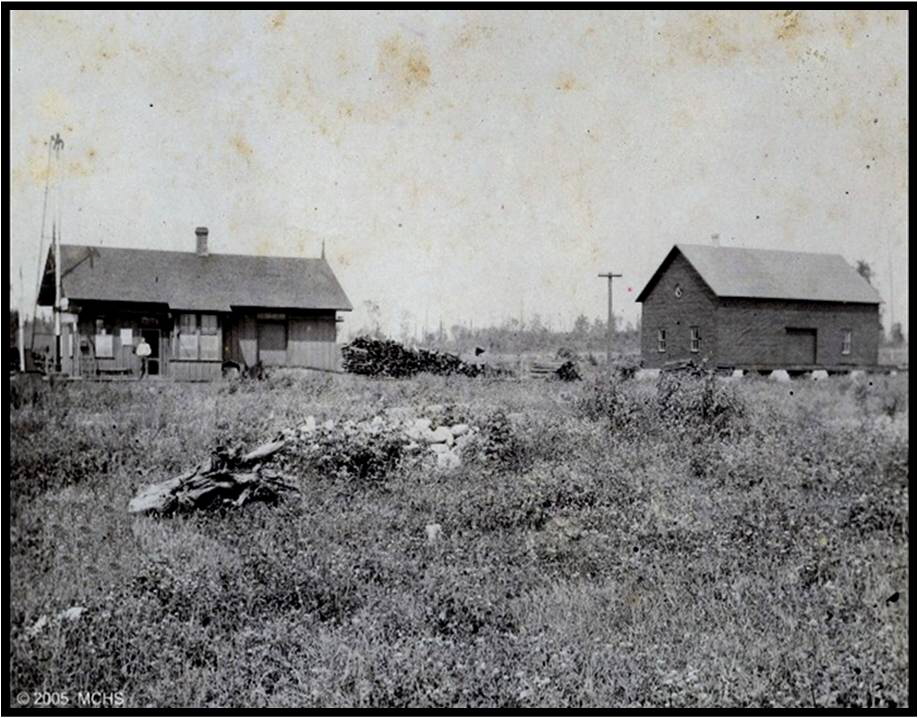

Despite this setback at the county level, the railroad persevered. The Town of Lincoln was persuaded to put up $6,000 in bonds and the Town of Adams to raise $10,000 to pay for construction–but only after the tracks reached Friendship. Right-of-way was acquired in Marquette and Adams counties; some high-visibility grading work southeast of Friendship–part of which later became Airport Drive–was completed. A depot site was selected on property then owned by J. W. Gunning at the south edge of the village in the vicinity of what is now Roseberry’s Funeral Home and the McGowan House Museum on South Main. Winn McGowan, who was a boy at the time, later recalled how thrilled he was at the thought of having a railroad run practically right up to the front door of his house. Once again, the county buzzed with talk of a railroad on its way, then stopped when buzz is all it turned out to be. No track was laid and the second “Princeton Line” turned out to be as much a phantom as the first.

All remained quiet on the railroad front until 1908-1909 when railroad talk revived with a frenzy, as well it should, since no fewer than five railroads were reportedly on their way to and through Adams County. “…from the number of promoters coming here,” reported the Adams County Press in October, 1908, “it may mean that there will be ‘something doing’.” The first would-be doer was H. L. Flanders, “a railroad promoter said to be connected with,” the Milwaukee Road. Flanders wanted to built a branch off the Milwaukee Road line from Fox Lake in Columbia county north to Montello, then west to Friendship and beyond with “bonding of the towns along the route.” The bonding did not come and neither did the Flanders railroad.

Next came the Western Transportation Company, a new operation headquartered in Portage which proposed building an “electro-gasoline” powered line from Portage to Briggsville, Big Spring, Easton, Friendship and Wisconsin Rapids–if county taxpayers would put up $75,000 in bonds. The promoter was a St. Paul contractor named J.N. Braun who toured town halls in the county to drum up support for the line. Local people were skeptical. As news editor Pierce wrote, Braun “asks us to share all the risk without presuming to have any backing…”

On the heels of the WTC, came the CWTC. Organized by J. J. Burns of Chicago, the new line was called the Central Wisconsin Transit Company. The CWTC pledged to lay track for a steam railroad from Kilbourn/Wisconsin Dells to Easton, Friendship, Big Flats and points north, if Adams county taxpayers could muster $100,000 in aid. With help from attorneys J. W. Purves and William Sweet of Friendship, the CWTC collected names on a petition to the county board containing “a majority of the male resident taxpayers,” signing in favor of paying $100,000 for railroad bonds. A skeptical county board hired attorney G. L. Williams of Wisconsin Rapids to investigate the CWTC and he found that the company was not incorporated until after it made its bonding proposal to Adams County. Although some railroad boosters argued that this was a technicality exploited by anti-railroad supervisors, bonds were not issued and the railroad was not built.

In the midst of these schemes, work was completed on the Kilbourn/Wisconsin Dells dam and hydropower plant. The 9,000 KW station churned out more electricity than its owners knew what to do with, so “prominent men located along the line of the proposed road” organized the Chicago and Wisconsin Valley Railway Company. It promised to run electrically-powered trains from Wausau to Portage, with stops at Stevens Point, Wisconsin Rapids, Big Flats Friendship, Easton and Big Spring. Among the “prominent men located along the line” were J.W. Purves of Friendship and the colorful A.D. “Appletree” Barnes, a prosperous Waupaca nurseryman who had recently purchased a few thousand acres of Big Flats. He promoted Big Flats as a latter- day Garden of Eden and wanted a railroad in town so others might share his vision–and buy his land. Barnes and company promised to start laying track if Adams County taxpayers would issue the requisite $100,000 in bonds. Once again lawyer Purves toured the town halls where he pointed out that “the projected Wisconsin Valley electric railway will be a great convenience and benefit to the country through which it is to run, and that it will encourage a development of natural resources which will contribute to its own prosperity.”

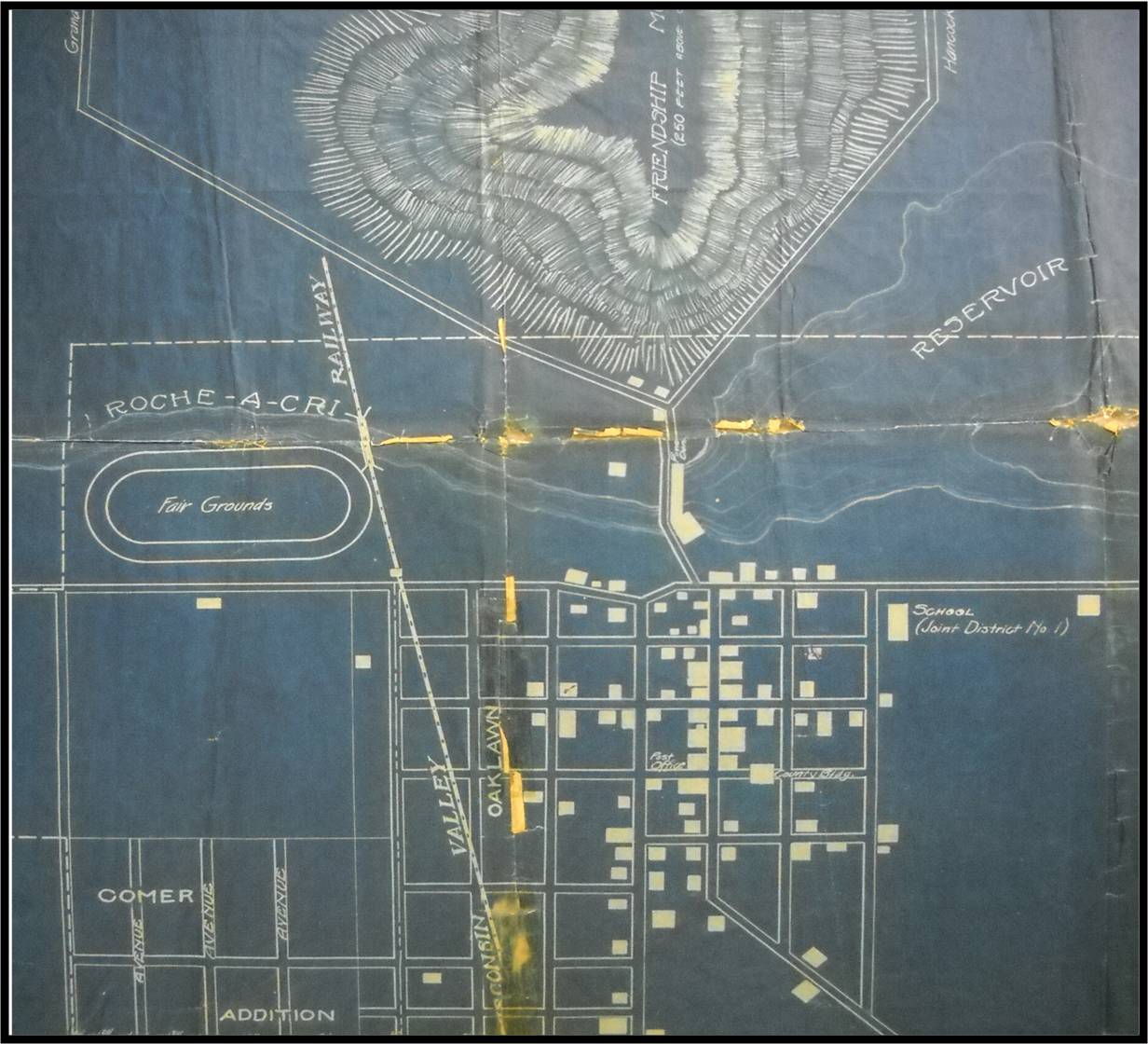

When no county aid appeared, the CWTC announced it would build without it, and survey work actually began early in 1910. The line was to cross the county from Briggsville to Easton, then proceed to the west side of Friendship village and Friendship Mound. Then it would head for Arkdale and jog over to the Barnes property in Big Flats, before heading north to Wisconsin Rapids. The electric line might actually have been built had the Chicago and North Western not begun building its line across the county in the spring of 1910. Electric interurban lines were being built across Wisconsin and the power from the Dells dam was eventually sold to run an electric railroad from Watertown to Milwaukee. Even then remnants of the CWTC survived as a local trolley line in Stevens Point, while in Adams County, Appletree Barnes continued to promote it as a looping spur to connect Friendship with the North Western depot south of the village.

While all these entrepreneurs maneuvered to entice money out of the taxpayers, the railroad that neither asked nor needed public aid went to work. The Chicago and North Western had built its main line between Milwaukee and St. Paul in the 1870s. It ran to Madison and Baraboo then into the hills on the way to Elroy, Sparta and La Crosse. It was a slow and tedious haul through the hills west of Elroy, and no longer suitable for through service with modern equipment. In addition, the North Western had outgrown its yards at the division point in Baraboo, and needed space to expand.

The North Western thereupon decided to build an entirely new line from the Lindwurm junction north of Milwaukee to Necedah where it would meet existing C & NW track from Wyeville. The Lindwurm-Wyeville portion of the line was designed as a through route and would not travel through any village with a population greater than 1,000. This was the railroad that would come to Adams County.

The Chicago and North Western Comes to Adams County

The story begins, as all railroad stories do, with a survey, in this case more than one. In 1893, the North Western had surveyed a route through Adams County for its “Princeton Line” which was to run northwest from Princeton, to Necedah via Friendship. In the summer of 1909, the North Western commissioned two crews to survey Adams County. One worked its way east from Carmon’s Rock in Strong’s Prairie, the other moved northwest from Oxford. Working out of tents pitched across the road from the fairgrounds, one crew went over the 1893 line which passed through the southwest part of Friendship. As they moved through Section 4, Town of Strong’s Prairie, and Section 16, Town of Adams, the surveyors, “deviated a little.” Shallow curves appeared in the line just east of what is now 16th Avenue and Dakota Avenues and about three-quarters of a mile south of what became County Highway M, halfway betwwen 11th and 10th Avenues. As reported by Harry Pierce in the Adams County Press, “the survey as now made makes the line run about a mile south of the village.” The deviation and its implications did not go unnoticed. “Whether the one just made or the original line coming through the village will be accepted, is not known,” Pierce continued. “This survey, as we understand, is the last…”

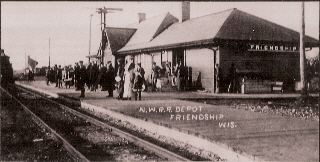

By November 1909, agents for the newly-incorporated Milwaukee, Sparta and North Western Railroad, aided by local railroad booster John Purves, were securing options on land for the right-of-way. One dollar down would hold a parcel for six months. One railroad agent “was heard to remark that a station would be built where the line crosses the north and south road south of town and its name would be Friendship.” After waiting for fifty years, Friendship would have a railroad station, but apparently not in Friendship.

As this realization dawned on the people of the village, most were concerned, a few were alarmed. In January 1910, a meeting was held in the office of County Attorney Charles Gilman, attended by the county’s leading lights of business and politics. George Bingham, Adams town board chair, school board member, builder of rural telephone lines, who would be elected to the legislature the following November, chaired the meeting. Alan Galbraith, future register of deeds who would enter the legislature in 1917, was secretary. The subject at hand was what to do about the railroad’s bypassing of Friendship.

Apparently, appeals to the railroad were ineffective, since the group decided to take the question to the Wisconsin Railroad Commission. A committee consisting of merchants Frank Higbee, Augustus Hill and John Gunning plus County Surveyor M. C. Smith and Attorney Gilman was delegated to attend an upcoming hearing of the Commission to state, “the village interests and…the best means to be used in gaining them.”

As it turned out, Gilman went to Madison with hotelier William Greenwood, storekeeper John B. Hill and Arkdale’s John Sullivan. The three

reported that the North Western would not correct its deviation from the 1893 survery and bring its main line to Friendship. However, “Vice-President Gardner…on the stand before the commission promised that the company would run a spur from the line a mile south of town into the village limits anywhere that a committee of citizens might designate.” He also promised to build a siding in Strong’s Prairie, “not over three miles from the village of Arkdale.”

Construction contracts totalling $10 million were signed in February since “building activities will commence with a rush with the opeing of spring.” In the Adams County Press, Harry Pierce declared that, “the appearance of the village will be materially changed…much more will be done than is now thought of…a boom will strike the town unprecedented in its history.”

The long-awaited boom was about to begin. However, before recounting the story of the railroad’s arrival and the birth of the city of Adams, attention should be paid to the first question of Adams County history. Why did the railroad not come to Friendship? As every newcomer is told, the railroad did not build to Friendship because landowners in and near the village demanded too high a price for their property. Friendship attorney John Purves, and the village’s leading merchants John Gunning, John Hill and his son Augustus, have been singled out for blame. The first storekeeper in Friendship and well up in years, John Hill was largely inactive in 1909, but Augustus was not and he did own acreage on the old North Western survey as did Purves. John Gunning owned even more land on the survey as well as the site at the end of Belfast Street where the “Princeton” line planned to locate its depot in 1901. So, if raising the price of their land could keep the railroad out of Friendship, Hill, Purves and Gunning were well-positioned to do it. Even if greed was not a factor, Gunning had good reason not to sell to the railroad. In 1907, he had built the largest and arguably the finest house in Friendship on the old survey at the end of Belfast Street. Should he have sold his dream house to the railroad?

On its part, the railroad was not managed by choir boys. It paid no more than necessary for right of way. For example, David and Emma McChesney were paid $90 and “the location of a station” for the 300 foot wide strip of property that became the heart of Grand Marsh. Chris Holm did better. He got $90 for a 200-foot strip where the Holmsville siding was built. Edwin and Mary Huber were more accommodating. They sold the 300 foot strip that became Brooks for “$1 plus location of a station on the land.” So maybe Hill and Gunning merely tried to strike a better– but not exorbitant–deal for themselves than the country folk did, and what they asked was still too much for the railroad.

Maybe price had nothing to do with the railroad’s choice of land. The survey of 1909 which “deviated” was completed before any land was optioned or purchased. Maybe the railroad laid its track away from Friendship because suitable land close to the village was not available. As the size of its Adams yard indicated, the North Western did require extensive acreage. Much of the land south of the old survey was low and wet and remained vacant for decades even after the railroad was built. So maybe the railroad built away from Friendship because there wasn’t enough high and dry land near to the village.

Be that as it may, the North Western did not come to Friendship and not everyone was unhappy about it. As Emma Barnes, Friendship postmaster in 1922, wrote in 1957, “I believe that the people of Friendship should express their appreciation of two of the early citizens…J.B. Hill and J.W. Purves…for holding the price of their land so high that the great C & NW R.R. Co. would not purchase a right of way…for who would enjoy the smoke and the noise of a train running hrough this beautiful village?”

4 Responses to Coming of the Railroad